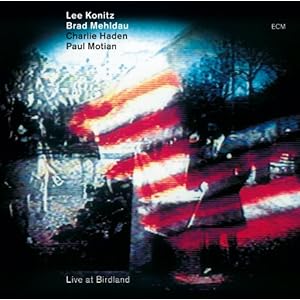

Lee Konitz has played in many different styles, from bop to cool to out, but he's now at that stage in his career where he plays it all and he plays none of it. Indeed, to hear him on this 2009 live date with this all-start rhythm section, he at first sounds like the liability—the old guy who has lost his tone and it playing slightly out of key. But a deeper listening reveals a saxophonist who is working intensely to discover the essence of every melody.

Konitz's impeccable bandmates respond with a sense of intense exploration and introspection. Live at Birdland contains six performances, and all but one are essentially ballads, allowing the players to work at a ruminative pace Inside these medium to slower tempos, the band is conversational and thoughtful, debating each chord, going off on tangents, making risky arguments or coming up with some daring theories. It is consistently fascinating listening, the kind that requires concentration and involvement.

Read my full review of Lee Konitz, Brad Mehldau, Charlie Haden, Paul Motian: Live at Birdland HERE.

The band’s other primary soloist is Mehldau, who acts as a useful contrast to Konitz. Mehldau is the relative rookie of the band—more than 30 years younger than each of his compatriots. He is, however, every bit as commanding and free. Unlike Konitz, he plays with a surface attractiveness of tone and touch that help his more daring explorations to go down easy. On most tunes, the listener also gets a healthy dose of Haden’s singing bass. The pairing of Haden and Motian is always empathetic and wonderful, and Haden is the most purely lovely player on this date. His solo on “You Stepped Out of a Dream” is logical and lyrical at once, and his statement on “Lullaby of Birdland” ingeniously uses the rhythms and intervals of the original melody to keep the improvisation focused and enchanting.

The quartet, taken as a whole, sets Konitz in good contrast and makes a compelling case that it’s more important what notes you choose than whether they are played with brilliant technique. Listening, for example, to Konitz and Motian improvise a duet on “Oleo” at first is a truly fascinating conversation. And when Mehldau joins, tartly and minimally, then Haden as well—you have a great band on your hands.

Header Quote

"If you ain't got it in you, you can't blow it out."

— Louis Armstrong

Monday, July 25, 2011

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Pat Metheny: Whats It All About

Pat Metheny and I grew up around the same time, and I remember listening to the pop music of the 1960s on AM radio, knowing even then that it was a lucky and good thing to be experiencing. There was "rock," sure, but this melodically and harmonically rich pop music was just as emblematic of the time—and if you let it do so, it could tie you back to the past too.

Metheny's latest disc, What's It All About (full review on PopMatters right HERE) is a solo acoustic guitar recital of these kinds of tunes, mostly played on a uniquely-tuned baritone acoustic guitar. (A few songs are played on nylon string guitar or the 42-string "Pikasso" guitar.) In being a solo acoustic recording, the record is a follow-up to Metheny's One Quiet Night from 2003. The tunes here, however, are also united by being from this unique era of songwriting.

So we get Pat playing Bacharach's "Alfie," which requires no reinterpretation or gimmickry. Metheny simply loses himself in the astonishing harmonies, pulling on melodic threads that unspool beautifully. (The failure of more jazz musicians to really absorb and explore the Bacharach catalog is hereby noted and lamented.) Similarly, the Stylistics "Betcha By Golly, Wow" is played simply but with a touch of swing, and Metheny's delicious voicings bring some new harmonies to the front in various places.

The most spare and surprising interpretation here is Metheny’s rethinking of Jobim’s “The Girl From Ipanema”. If you are like me, then you have heard this bossa nova chestnut played in countless piano bars, usually with an insulting anonymity. Metheny conceives it as a minimal exercise, using just a fragment of the melody and emphasizing a series of new harmonies that allow him to explore the texture and resonance of his instrument. If you release your expectations, then your ear will hang on every note and every fresh chord.

In addition, the album features the surf-rock classic "Pipeline", "The Sounds of Silence", "And I Love Her", and "The Girl from Ipanema", among other '60s tunes. Some listeners will find too fluffy, to noodly, but they're wrong. What's It All About is a beautiful statement, and not less good because it is mostly simple.

Metheny's latest disc, What's It All About (full review on PopMatters right HERE) is a solo acoustic guitar recital of these kinds of tunes, mostly played on a uniquely-tuned baritone acoustic guitar. (A few songs are played on nylon string guitar or the 42-string "Pikasso" guitar.) In being a solo acoustic recording, the record is a follow-up to Metheny's One Quiet Night from 2003. The tunes here, however, are also united by being from this unique era of songwriting.

So we get Pat playing Bacharach's "Alfie," which requires no reinterpretation or gimmickry. Metheny simply loses himself in the astonishing harmonies, pulling on melodic threads that unspool beautifully. (The failure of more jazz musicians to really absorb and explore the Bacharach catalog is hereby noted and lamented.) Similarly, the Stylistics "Betcha By Golly, Wow" is played simply but with a touch of swing, and Metheny's delicious voicings bring some new harmonies to the front in various places.

The most spare and surprising interpretation here is Metheny’s rethinking of Jobim’s “The Girl From Ipanema”. If you are like me, then you have heard this bossa nova chestnut played in countless piano bars, usually with an insulting anonymity. Metheny conceives it as a minimal exercise, using just a fragment of the melody and emphasizing a series of new harmonies that allow him to explore the texture and resonance of his instrument. If you release your expectations, then your ear will hang on every note and every fresh chord.

In addition, the album features the surf-rock classic "Pipeline", "The Sounds of Silence", "And I Love Her", and "The Girl from Ipanema", among other '60s tunes. Some listeners will find too fluffy, to noodly, but they're wrong. What's It All About is a beautiful statement, and not less good because it is mostly simple.

Monday, July 11, 2011

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: The Sesjun Radio Shows

Between 1978 and 1983, the drummer Art Blakey had his great band, the Jazz Messengers, in serious transition. The mid-1970s had not been a great era for the band (or for mainstream jazz as a whole), and he was shaking the group out of a doldrums with an infusion of new young players.

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: The Sesjun Radio Shows (read my full PopMatters review HERE) brings to light three recordings of European concerts from this time that have never been released before. The music is exciting and vibrant, particularly the playing of alto saxophonist (and band music director for much of this period) Bobby Watson. Watson's solos have swagger and swing, and his sound is drenched in blues that way the sound of a guy from Kansas City should be. Watson is also a featured composer, and his "E.T.A." is one of the highlights.

Also well-represented here is the great two-fisted piano player James Williams. Williams was the most down-home Messenger pianist since Bobby Timmons, and his playing here can be both harmonically rich and simply direct. As with Watson, his tunes ("1977 A.D.", for example) are among the freshest on the date.

This record is also a reason to reconsider the Messenger legacy of trumpeter Valerie Ponomerev. He had a long tenure with the band, but I'd mostly thought of him as the placeholder until Wynton Marsalis came along in 1981-82. That is probably unfair. He acquits himself nicely in the first of the three concerts here (the third featuring Terence Blanchard, who replaced Marsalis), particularly with his ballad playing. Still, it remains that the bands feature Ponomerev and tenor player David Schnitter, while exciting, does not play with the polish and snap that would come to the ensemble once Wynton and brother Branford Marsalis came along.

But more Art Blakey is good for the world, particularly now that he's gone and jazz no longer has a mainstay such as the Messengers to be creating crackling hard bop. This release is more than welcome.

Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers: The Sesjun Radio Shows (read my full PopMatters review HERE) brings to light three recordings of European concerts from this time that have never been released before. The music is exciting and vibrant, particularly the playing of alto saxophonist (and band music director for much of this period) Bobby Watson. Watson's solos have swagger and swing, and his sound is drenched in blues that way the sound of a guy from Kansas City should be. Watson is also a featured composer, and his "E.T.A." is one of the highlights.

|

| Bobby Watson |

This record is also a reason to reconsider the Messenger legacy of trumpeter Valerie Ponomerev. He had a long tenure with the band, but I'd mostly thought of him as the placeholder until Wynton Marsalis came along in 1981-82. That is probably unfair. He acquits himself nicely in the first of the three concerts here (the third featuring Terence Blanchard, who replaced Marsalis), particularly with his ballad playing. Still, it remains that the bands feature Ponomerev and tenor player David Schnitter, while exciting, does not play with the polish and snap that would come to the ensemble once Wynton and brother Branford Marsalis came along.

But more Art Blakey is good for the world, particularly now that he's gone and jazz no longer has a mainstay such as the Messengers to be creating crackling hard bop. This release is more than welcome.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

JAZZ TODAY: Does TREME Hate Modern Jazz?

I'm a huge fan of Treme, the brilliant David Simon show on HBO about post-Katrina New Orleans. While it is very different in tone from The Wire, Simon's new show (which just finished its second season a week ago) is similar in that it takes as its subject the culture of an American city. And the culture of New Orleans is centrally about music.

Again, I love the show. I love music featured on the show—which is primarily the blessed soul and R'n'B that is associated with greats such as Professor Longhair and Allen Toussaint.

But as a jazz critic, it is somewhat disconcerting to me that the show sets up jazz—or, at least, "modern jazz" as it has existed since the 1950s with its world capitol being New York—as a kind of villain. It is, symbolically if not explicitly, the essence of soullessness and the embodiment of abandoning "home." The character on the show who plays modern jazz, Delmond, is the son of the chief of a Mardi Gras "Indian" tribe who cannot really accept his son's version of New Orleans's great music.

The way jazz is used in the story is complex and fascinating, and I hardly mean to suggest that David Simon himself or the show's other creators actually "hate" jazz, but there's no question that the show uses jazz as a stand-in for the abandonment of certain core traditions—and therefore for the abandonment of New Orleans itself as a city that needs to be rescued after tragedy. Compared to Antoine Batiste, the warm and wonderful trombone player who starts his own "Soul Apostles" band or to Annie and Harley, street musicians from a larger folk tradition who use music to understand or seek their personal identities, Delmond seems like a spoiled kid in a fancy suit who plays music of technical but not heartfelt appeal.

Read my full essay on the topic HERE at PopMatters.

Ultimately, Treme ends its second season (another has been ordered by HBO—yes!) by allowing Delmond and his dad to bring together modern jazz and traditional Mardi Gras music in a fascinating hybrid. However, the price of such coming together is that Delmond leaves New York to move back to New Orleans and seems to have conceded that his father was right that this music simply could not be made outside of New Orleans.

It's more complicated than that, sure, but my point is this: modern jazz takes it on the chin as cold and boring, a kind of music that people just don't like or that requires you to "think" too much rather than just enjoy. That is unfair to jazz, which remains a passionate, diverse music that goes well beyond mere technical execution. And it's a slightly lazy sign of the times that reminds me of political appeals that hold up for derision people with good educations in favor of "folksier" types to can "relate to regular people."

Not that I think David Simon is some kind of George Bush fan—hardly. But the rigors of modern jazz can be thrilling too. On that point, just a little, Treme is off key.

Again, I love the show. I love music featured on the show—which is primarily the blessed soul and R'n'B that is associated with greats such as Professor Longhair and Allen Toussaint.

But as a jazz critic, it is somewhat disconcerting to me that the show sets up jazz—or, at least, "modern jazz" as it has existed since the 1950s with its world capitol being New York—as a kind of villain. It is, symbolically if not explicitly, the essence of soullessness and the embodiment of abandoning "home." The character on the show who plays modern jazz, Delmond, is the son of the chief of a Mardi Gras "Indian" tribe who cannot really accept his son's version of New Orleans's great music.

The way jazz is used in the story is complex and fascinating, and I hardly mean to suggest that David Simon himself or the show's other creators actually "hate" jazz, but there's no question that the show uses jazz as a stand-in for the abandonment of certain core traditions—and therefore for the abandonment of New Orleans itself as a city that needs to be rescued after tragedy. Compared to Antoine Batiste, the warm and wonderful trombone player who starts his own "Soul Apostles" band or to Annie and Harley, street musicians from a larger folk tradition who use music to understand or seek their personal identities, Delmond seems like a spoiled kid in a fancy suit who plays music of technical but not heartfelt appeal.

|

| Delmond, the modern jazz player on TREME |

Ultimately, Treme ends its second season (another has been ordered by HBO—yes!) by allowing Delmond and his dad to bring together modern jazz and traditional Mardi Gras music in a fascinating hybrid. However, the price of such coming together is that Delmond leaves New York to move back to New Orleans and seems to have conceded that his father was right that this music simply could not be made outside of New Orleans.

It's more complicated than that, sure, but my point is this: modern jazz takes it on the chin as cold and boring, a kind of music that people just don't like or that requires you to "think" too much rather than just enjoy. That is unfair to jazz, which remains a passionate, diverse music that goes well beyond mere technical execution. And it's a slightly lazy sign of the times that reminds me of political appeals that hold up for derision people with good educations in favor of "folksier" types to can "relate to regular people."

Not that I think David Simon is some kind of George Bush fan—hardly. But the rigors of modern jazz can be thrilling too. On that point, just a little, Treme is off key.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)