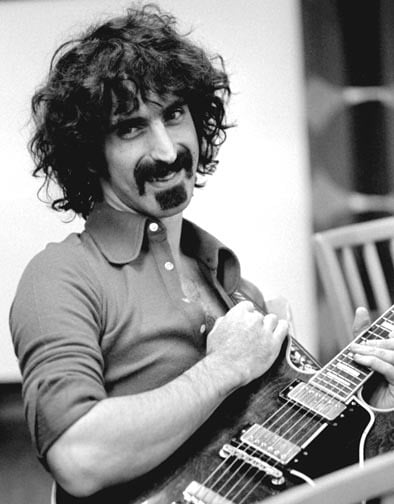

As a young jazz fan growing up in the 1970s, I had an inevitable fascination with the music of Frank Zappa. For me, Zappa was a kind of jazz musician. This was before Zappa was mainly known for chiding the Parents Music Resource Center, of course, but it roughly coincides with a time when Zappa was known to teenagers for a being a kind of novelty song guy. 1974's "Don't Eat Yellow Snow" (from Apostrophe) was even on the radio.

But for me Zappa was synonymous with his 1971-72 albums Waka/Jawaka and The Grand Wazoo, which were mainly instrumental and seemed like everything I loved about jazz at the time, plus a whole lot of what was cool about that classic-era in rock. To a 13 year-old boy, in short, HEAVEN. (Also, I was obsessed with Jean-Luc Ponty's 1969 record King Kong: Jean-Luc Ponty Plays the Music of Frank Zappa, on which the budding fusion violinist played Frank's tunes with Frank on guitar. So hip!)

And I still feel that way about Zappa. He was the smartest, funniest, most serious, most not-taking-himself-seriously guy in music. And yet he took his music very seriously.

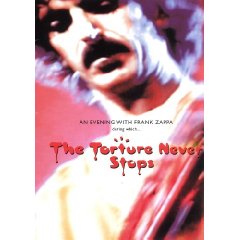

'An Evening with Frank Zappa, The Torture Never Stops' (reviewed by me here on PopMatters) is a DVD containing the complete, Zappa-produced footage of a concert at New York's Palladium Theater on Halloween, 1981. What a band! Steve Vai is searing on guitar, and Chad Wackerman is doing everything on drums. They play tunes from all across the Zappa spectrum to that point, with Zappa singing a bit, playing his guitar a bit, and also doing plenty of conducting with a baton. The music is literally non-stop, as one tune runs directly into the next in perfect, super-precise succession.

Seeing the music made before your eyes will renew your sense of how complex and detailed Zappa's music was. The rippling runs on harmonized marimba and electric guitar and analog synth send chills down your spine. At least they do to mine.

I still love Frank and his music. Here is a great walloping, live dose of it. Delicious!

Header Quote

"If you ain't got it in you, you can't blow it out."

— Louis Armstrong

Thursday, April 28, 2011

Monday, April 18, 2011

The World Saxophone Quartet: Yes We Can

Old things can be new again.

And in jazz, too few bands stick around for thirty years. Certainly there are too few edgy bands that stick around for decades without losing their bracing newness. But the World Saxophone Quartet is just that. Begun in 1976, the WSQ has always functioned on the avant-garde wing of jazz but with tremendous success and showmanship. For all its honking and squealing, the WSQ has also covered Jimi Hendrix and Duke Ellington, making it for a long time on Elektra/Nonesuch. The band, which normally plays as just four saxophones with no rhythm section, long ago achieved a balance between the daring and the structured.

Yes We Can (read my PopMatters full review HERE) finds the band live in concert, playing alone and without frills. Things are not just as they were in '76, however. Julius Hemphill passed a while ago, and he is replaced here by the band's newest permanent member, the thrilling James Carter. Replacing Oliver Lake for a few concerts was Kidd Jordan, the New Orleans veteran who originally brought the band together. Founding members David Murray and Hamiet Bluiett are on hand and holding down the traditional sound.

Things start, as they always did when I saw the band live in the past, with Bluiett's "Hattie Wall," grounding things in a stomping groove rather than just abstraction. But this program then moves into fresh territory: something wild from Jordan, a lovely ballad from Murray that has the WSQ sounding like a lovely, harmonized chorus, "The Guessing Game" from Bluiett that takes advantage of the band's facility with pastel clarinet sounds.

This is a solid WSQ record in the classic mode. No African drummers or R 'n' B covers, which were both cool things for the band but not its bread and butter. Yes We Can, which of course refers to the US election of Barack Obama, find the band content and solid but also new, looking to the past but happily grounded in the present. It's a good place to discover the band if you don't know it, and it's a good place to come back to if you're an old fan who hasn't heard these boys in a while.

And in jazz, too few bands stick around for thirty years. Certainly there are too few edgy bands that stick around for decades without losing their bracing newness. But the World Saxophone Quartet is just that. Begun in 1976, the WSQ has always functioned on the avant-garde wing of jazz but with tremendous success and showmanship. For all its honking and squealing, the WSQ has also covered Jimi Hendrix and Duke Ellington, making it for a long time on Elektra/Nonesuch. The band, which normally plays as just four saxophones with no rhythm section, long ago achieved a balance between the daring and the structured.

Yes We Can (read my PopMatters full review HERE) finds the band live in concert, playing alone and without frills. Things are not just as they were in '76, however. Julius Hemphill passed a while ago, and he is replaced here by the band's newest permanent member, the thrilling James Carter. Replacing Oliver Lake for a few concerts was Kidd Jordan, the New Orleans veteran who originally brought the band together. Founding members David Murray and Hamiet Bluiett are on hand and holding down the traditional sound.

Things start, as they always did when I saw the band live in the past, with Bluiett's "Hattie Wall," grounding things in a stomping groove rather than just abstraction. But this program then moves into fresh territory: something wild from Jordan, a lovely ballad from Murray that has the WSQ sounding like a lovely, harmonized chorus, "The Guessing Game" from Bluiett that takes advantage of the band's facility with pastel clarinet sounds.

This is a solid WSQ record in the classic mode. No African drummers or R 'n' B covers, which were both cool things for the band but not its bread and butter. Yes We Can, which of course refers to the US election of Barack Obama, find the band content and solid but also new, looking to the past but happily grounded in the present. It's a good place to discover the band if you don't know it, and it's a good place to come back to if you're an old fan who hasn't heard these boys in a while.

Friday, April 15, 2011

Paul Simon: So Beautiful or So What

There has always been more to Simon than what was easily embraced, and that work—including his new, scintillating So Beautiful or So What—is much of his finest music.

The sound of So Beautiful is a kaleidoscope that moves from throbbing Graceland guitar to South Asian grooves on tablas to gentle ballads that incorporate harps, to outright rockers that are nevertheless flavored with bluegrass elements or even subtle atmospherics such as the sound of ringing phones, an old sermon, or an atonal glockenspiel. These elements, however, are juggled and mixed with great care and balance. So Beautiful is a not a pu-pu platter of styles but rather a summation of a great musician’s many interests. It coheres because the sounds serve the songs.

And the songs themselves are united utterly, thematically obsessed with the largest and most intriguing questions that art can tackle. Read my full PopMatters review of So Beautiful or So What right HERE.

By all accounts, Paul Simon—born in Newark, NJ, as a Jew during World War II—isn’t a deeply religious man. But So Beautiful relentlessly comes back to the notion of God (and frequently a Christian God) and to the value of love. But this is not the equivalent of Dylan’s born-again Slow Train Coming. Rather, Simon uses Christian iconography to raise spiritual questions of the most philosophical sort: Is there an order to life? Is there anything beyond this life? Are there sure answers to important questions? What redeems us, flawed though we are?

At least two songs here seem like outright Simon classics. “Getting Ready for Christmas Day” sets up a strange delta groove, and Simon’s sung verses about regular folks facing Christmas amidst adversity alternate with segments of an old sermon (with the call-and-response of a congregation) about both the terror and the glory of what might be waiting for various people. It’s an ingenious and ambiguous piece of art.

Even better is “Questions for the Angels”, a song that begins as an impossibly lovely song about a “pilgrim” wandering through New York. On the one hand, it is a very specific story song, and on the other hand it gets to abstractions such as “Who am I in this lonely world?” The song shifts halfway through to become a jaunty waltz, but that is just how Simon hears his music now—unrestricted and able to surprise you even as it casts a specific spell.

So Beautiful or So What is a complete classic—an album in which to lose yourself even as you get found.

The sound of So Beautiful is a kaleidoscope that moves from throbbing Graceland guitar to South Asian grooves on tablas to gentle ballads that incorporate harps, to outright rockers that are nevertheless flavored with bluegrass elements or even subtle atmospherics such as the sound of ringing phones, an old sermon, or an atonal glockenspiel. These elements, however, are juggled and mixed with great care and balance. So Beautiful is a not a pu-pu platter of styles but rather a summation of a great musician’s many interests. It coheres because the sounds serve the songs.

And the songs themselves are united utterly, thematically obsessed with the largest and most intriguing questions that art can tackle. Read my full PopMatters review of So Beautiful or So What right HERE.

By all accounts, Paul Simon—born in Newark, NJ, as a Jew during World War II—isn’t a deeply religious man. But So Beautiful relentlessly comes back to the notion of God (and frequently a Christian God) and to the value of love. But this is not the equivalent of Dylan’s born-again Slow Train Coming. Rather, Simon uses Christian iconography to raise spiritual questions of the most philosophical sort: Is there an order to life? Is there anything beyond this life? Are there sure answers to important questions? What redeems us, flawed though we are?

At least two songs here seem like outright Simon classics. “Getting Ready for Christmas Day” sets up a strange delta groove, and Simon’s sung verses about regular folks facing Christmas amidst adversity alternate with segments of an old sermon (with the call-and-response of a congregation) about both the terror and the glory of what might be waiting for various people. It’s an ingenious and ambiguous piece of art.

Even better is “Questions for the Angels”, a song that begins as an impossibly lovely song about a “pilgrim” wandering through New York. On the one hand, it is a very specific story song, and on the other hand it gets to abstractions such as “Who am I in this lonely world?” The song shifts halfway through to become a jaunty waltz, but that is just how Simon hears his music now—unrestricted and able to surprise you even as it casts a specific spell.

So Beautiful or So What is a complete classic—an album in which to lose yourself even as you get found.

Thursday, April 14, 2011

JAZZ TODAY: An Infectious Case of Jazz Fanaticism

A month ago I was in New York for work and had the chance to go the late night "Spontaneous Construction" show at The Blue Note. It was going to be a great, if crazy, show—an unrehearsed band featuring free tenor player Joe McPhee and drummer Nasheet Waits, along with cellist Marika Hughes and the bass player John Hebert. Fun.

A month ago I was in New York for work and had the chance to go the late night "Spontaneous Construction" show at The Blue Note. It was going to be a great, if crazy, show—an unrehearsed band featuring free tenor player Joe McPhee and drummer Nasheet Waits, along with cellist Marika Hughes and the bass player John Hebert. Fun.The only issue was that I felt like I should invite my co-workers—but how likely were they to dig some real "eek-onk" music: free blowing with not set melodies and plenty of atonality? If if they hated it, well, you know the way that can compromise your own enjoyment. Still, two adventurous colleagues were ready for the thrill and downtown we went.

You can read the whole tale, and a bit about the group that puts on "Spontaneous Construction", in my latest JAZZ TODAY column, here: An Infectious Case of Jazz Fanaticism.

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

Ambrose Akinmusire: When the Heart Emerges Glistening

The new Blue Note album by Ambrose Akinmusire, When the Heart Emerges Glistening, is a complete knock-out. Here is my PopMatters review, in total:

Thirty years ago, in 1981, a young trumpeter made his first statement on a major label and blew listeners out of their seats. When Wynton Marsalis debuted on Columbia, it was legitimate to say that you had never heard anyone play with such quicksilver fluency. It wasn’t that the music itself was daringly original but that Marsalis’s voice on the instrument seemed like a sudden, dramatic upgrade in brilliance.

The 2011 Blue Note debut of Ambrose Akinmusire has a similar power and excitement. Akinmusire is older (28), and he already released a very good disc on Fresh Sound New Talent (Prelude to Cora). But it remains that When the Heart Emerges Glistening is a thrilling, dazzling debut—the emergence of a new voice in the music and a new sound and conception for the trumpet.

Akinmusire doesn’t come out of nowhere. He played with Steve Coleman’s Five Elements band out of high school, he attended the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz in LA, then he won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition. Akinmusire was on the radar. A jazz fan might have seen him coming. But our ears still weren’t ready.

So, what’s so special about this trumpet player? Akinmusire combines three brilliant instrumental merits: a virtuosity of speed and fluency, an ability to generate new kinds of patterns and intervals and a freshly conceived approach to sound.

Akinmusire doesn’t show off by playing fast and high, necessarily. But he moves like a ninja through an alleyway—slippery and precise, in front of you, then behind you, then beyond you. His playing on the original “The Walls of Lechuguilla” is flabbergasting. The trumpet-only introduction is like nothing you have heard before. Akinmusire toggles between two notes, playing the higher note with a deadened sound, then begins dropping the lower note micro-tonally Then he starts speeding up the pattern, then complicating it until it is a spiraling flurry. If it reminds you a bit of Lester Bowie, but also a bit of Dizzy Gillespie, then you’re hearing the kind of thrill that I am. It also brings to mind, just a bit, Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues” as the whole exercise ultimately fuses brilliantly into the composition itself, continuing as a fascinating and percussive dialogue with a great rhythm section.

On this tune alone, Akinmusire demonstrates that he is playing in an original jazz trumpet voice. He monkeys with tone and note choice, but he does it at crackerjack tempo. You might be so taken with the dazzle of it all that you don’t realize that he does it all in the service of the composition. But, amazingly, he has that base covered too.

The opening tune, “Confessions to My Unborn Daughter”, is nearly as fine. Another introductory trumpet cadenza draws you in with unsettling originality, and then the band makes sense of it all with a grooving but stately triple meter. The rhythm section (pianist Gerald Clayton, bassist Harish Raghavan, and drummer Justin Brown) locks in with a blend of jazz complexity and pop instinct. Like the finest bands out there today, these guys blend the elaborate dialogue of jazz with a stuttering edge of hip hop punch. And then there is tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, who plays like he is wired into Akinmusire’s brain directly. The two are twinned up like an Ornette Coleman/Don Cherry for the new era.

On “Confessions” and on “Henya”, there are moments where the two horn players, separately but also together, bend and choke their notes like virtuoso singers who operate without the boundaries of traditional scales or Western instruments. It might seem kind of avant-garde if it weren’t so utterly beautiful. It’s not bold as much as it is breathtaking. When the Heart Emerges Glistening isn’t a manifesto; it’s just great.

Akinmusire’s compositions are appealing, but they often have the jagged trickiness of his mentor Steve Coleman. “Far But Few Between” starts with a series of interval jabs by trumpet which are then answered by a rhythm section pattern that is so skitteringly complex that it seems improvised beyond a time signature (though I’m quite certain it is predetermined). “Jaya” is a mid-tempo groove tune based on a time pattern that sounds perfectly natural but that non-experts will hardly be able to discern. Remarkable it is, then, that these songs are not in the least forbidding or unappealing. Indeed, like all of Glistening, these tunes seem as easy to enjoy as anything from Wynton Marsalis or from a basic mid-60s Blue Note album.

A couple of tracks have notably different formats. “Ayneh (Cora)” is a delicate duet for piano (Clayton) and celeste (Akinmusire). The two also duet on “Ayneh (Campbell)” and “Regret (No More)”, where Akinmusire’s trumpet control—his mastery of tone and pure sound—serves a heartfelt melody. “My Name is Oscar” is a duet for Akinmusire’s spoken-word evocation of a police shooting in his hometown of Oakland, Calif., and Brown’s drums. Clean and powerful, it works.

Tellingly, Akinmusire includes only one standard in this recital: “What’s New”, also a duet. The feeling is outwardly more traditional, with Clayton playing in a modern stride style. But even here, the leader sounds fully up-to-the-minute, not aping his hero Clifford Brown but, instead, suggesting that Brown’s legacy is arcing into the future, decades after it seemed like there might be no new way to play “mainstream” jazz.

Kudos to Blue Note president Bruce Lundvall for getting Ambrose Akinmusire and his band into the studio. And kudos to pianist Jason Moran for not only suggesting this but also producing the recording (and playing Rhodes, subtly and beautifully, on a couple of tracks).

When the Heart Emerges Glistening is a gem. It’s a jazz record to rave about and to push on your friends. It’s the product of a talent that should send shivers up every jazz fan’s spine. Ambrose Akinmusire has been holding back, finding his voice, developing his band, and now he is here in full bloom.

Spring has arrived. You can feel it in your bones, and now you can hear it with your ears.

Thirty years ago, in 1981, a young trumpeter made his first statement on a major label and blew listeners out of their seats. When Wynton Marsalis debuted on Columbia, it was legitimate to say that you had never heard anyone play with such quicksilver fluency. It wasn’t that the music itself was daringly original but that Marsalis’s voice on the instrument seemed like a sudden, dramatic upgrade in brilliance.

The 2011 Blue Note debut of Ambrose Akinmusire has a similar power and excitement. Akinmusire is older (28), and he already released a very good disc on Fresh Sound New Talent (Prelude to Cora). But it remains that When the Heart Emerges Glistening is a thrilling, dazzling debut—the emergence of a new voice in the music and a new sound and conception for the trumpet.

Akinmusire doesn’t come out of nowhere. He played with Steve Coleman’s Five Elements band out of high school, he attended the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz in LA, then he won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition. Akinmusire was on the radar. A jazz fan might have seen him coming. But our ears still weren’t ready.

So, what’s so special about this trumpet player? Akinmusire combines three brilliant instrumental merits: a virtuosity of speed and fluency, an ability to generate new kinds of patterns and intervals and a freshly conceived approach to sound.

Akinmusire doesn’t show off by playing fast and high, necessarily. But he moves like a ninja through an alleyway—slippery and precise, in front of you, then behind you, then beyond you. His playing on the original “The Walls of Lechuguilla” is flabbergasting. The trumpet-only introduction is like nothing you have heard before. Akinmusire toggles between two notes, playing the higher note with a deadened sound, then begins dropping the lower note micro-tonally Then he starts speeding up the pattern, then complicating it until it is a spiraling flurry. If it reminds you a bit of Lester Bowie, but also a bit of Dizzy Gillespie, then you’re hearing the kind of thrill that I am. It also brings to mind, just a bit, Louis Armstrong’s “West End Blues” as the whole exercise ultimately fuses brilliantly into the composition itself, continuing as a fascinating and percussive dialogue with a great rhythm section.

On this tune alone, Akinmusire demonstrates that he is playing in an original jazz trumpet voice. He monkeys with tone and note choice, but he does it at crackerjack tempo. You might be so taken with the dazzle of it all that you don’t realize that he does it all in the service of the composition. But, amazingly, he has that base covered too.

The opening tune, “Confessions to My Unborn Daughter”, is nearly as fine. Another introductory trumpet cadenza draws you in with unsettling originality, and then the band makes sense of it all with a grooving but stately triple meter. The rhythm section (pianist Gerald Clayton, bassist Harish Raghavan, and drummer Justin Brown) locks in with a blend of jazz complexity and pop instinct. Like the finest bands out there today, these guys blend the elaborate dialogue of jazz with a stuttering edge of hip hop punch. And then there is tenor saxophonist Walter Smith III, who plays like he is wired into Akinmusire’s brain directly. The two are twinned up like an Ornette Coleman/Don Cherry for the new era.

On “Confessions” and on “Henya”, there are moments where the two horn players, separately but also together, bend and choke their notes like virtuoso singers who operate without the boundaries of traditional scales or Western instruments. It might seem kind of avant-garde if it weren’t so utterly beautiful. It’s not bold as much as it is breathtaking. When the Heart Emerges Glistening isn’t a manifesto; it’s just great.

Akinmusire’s compositions are appealing, but they often have the jagged trickiness of his mentor Steve Coleman. “Far But Few Between” starts with a series of interval jabs by trumpet which are then answered by a rhythm section pattern that is so skitteringly complex that it seems improvised beyond a time signature (though I’m quite certain it is predetermined). “Jaya” is a mid-tempo groove tune based on a time pattern that sounds perfectly natural but that non-experts will hardly be able to discern. Remarkable it is, then, that these songs are not in the least forbidding or unappealing. Indeed, like all of Glistening, these tunes seem as easy to enjoy as anything from Wynton Marsalis or from a basic mid-60s Blue Note album.

A couple of tracks have notably different formats. “Ayneh (Cora)” is a delicate duet for piano (Clayton) and celeste (Akinmusire). The two also duet on “Ayneh (Campbell)” and “Regret (No More)”, where Akinmusire’s trumpet control—his mastery of tone and pure sound—serves a heartfelt melody. “My Name is Oscar” is a duet for Akinmusire’s spoken-word evocation of a police shooting in his hometown of Oakland, Calif., and Brown’s drums. Clean and powerful, it works.

Tellingly, Akinmusire includes only one standard in this recital: “What’s New”, also a duet. The feeling is outwardly more traditional, with Clayton playing in a modern stride style. But even here, the leader sounds fully up-to-the-minute, not aping his hero Clifford Brown but, instead, suggesting that Brown’s legacy is arcing into the future, decades after it seemed like there might be no new way to play “mainstream” jazz.

Kudos to Blue Note president Bruce Lundvall for getting Ambrose Akinmusire and his band into the studio. And kudos to pianist Jason Moran for not only suggesting this but also producing the recording (and playing Rhodes, subtly and beautifully, on a couple of tracks).

When the Heart Emerges Glistening is a gem. It’s a jazz record to rave about and to push on your friends. It’s the product of a talent that should send shivers up every jazz fan’s spine. Ambrose Akinmusire has been holding back, finding his voice, developing his band, and now he is here in full bloom.

Spring has arrived. You can feel it in your bones, and now you can hear it with your ears.

Friday, April 1, 2011

Willie Nelson and Wynton Marsalis featuring Norah Jones: Here We Go Again

If it ain't broke, don't fix it. A-and, add Norah Jones to the mix as well.

In 2008, Blue Note released a live recording from Wynton Marsalis featuring the timeless Willie Nelson as guest singer and soloist. Two Men with the Blues was one of the highlights of that year because Nelson made the sometimes antiseptic Marsalis (with a crack quintet) looser and more fun and Marsalis pushed the sometimes-rather-lazy Nelson to be sharper. It was a classic win-win.

The boys are back together again with Here We Go Again (read my full PopMatters review here). And it's another strong outing. How could it not be, with the material this time being the stellar repertoire associated with Ray Charles and with the single-malt voice of Norah Jones featured as well? Again, Marsalis's arrangements for quintet are clever and swinging, astutely recasting familiar material in smart ways. And Nelson proves again that his laconic singing style is as much a child of Louis Armstrong as any proper "jazz" singer. Finally, this is the first we've gotten to hear Jones singing with a true jazz group behind (rather than merely her fine but limited pop band), and Marsalis spurs her singing to a higher realm. (Seriously, why hasn't Norah Jones made a real jazz album?)

The boys are back together again with Here We Go Again (read my full PopMatters review here). And it's another strong outing. How could it not be, with the material this time being the stellar repertoire associated with Ray Charles and with the single-malt voice of Norah Jones featured as well? Again, Marsalis's arrangements for quintet are clever and swinging, astutely recasting familiar material in smart ways. And Nelson proves again that his laconic singing style is as much a child of Louis Armstrong as any proper "jazz" singer. Finally, this is the first we've gotten to hear Jones singing with a true jazz group behind (rather than merely her fine but limited pop band), and Marsalis spurs her singing to a higher realm. (Seriously, why hasn't Norah Jones made a real jazz album?)

What's missing from Here We Go Again is pretty well implied by the title—it's a bit routine. You know these songs a little too well, and everyone involved is doing what they do perfectly on cue. This disc doesn't seem to have a capacity to surprise us.

That said, it's lovely in nearly every way—a great example of how jazz can still be a powerful popular medium. It's a jazz album that I think just about anyone should delight in.

In 2008, Blue Note released a live recording from Wynton Marsalis featuring the timeless Willie Nelson as guest singer and soloist. Two Men with the Blues was one of the highlights of that year because Nelson made the sometimes antiseptic Marsalis (with a crack quintet) looser and more fun and Marsalis pushed the sometimes-rather-lazy Nelson to be sharper. It was a classic win-win.

The boys are back together again with Here We Go Again (read my full PopMatters review here). And it's another strong outing. How could it not be, with the material this time being the stellar repertoire associated with Ray Charles and with the single-malt voice of Norah Jones featured as well? Again, Marsalis's arrangements for quintet are clever and swinging, astutely recasting familiar material in smart ways. And Nelson proves again that his laconic singing style is as much a child of Louis Armstrong as any proper "jazz" singer. Finally, this is the first we've gotten to hear Jones singing with a true jazz group behind (rather than merely her fine but limited pop band), and Marsalis spurs her singing to a higher realm. (Seriously, why hasn't Norah Jones made a real jazz album?)

The boys are back together again with Here We Go Again (read my full PopMatters review here). And it's another strong outing. How could it not be, with the material this time being the stellar repertoire associated with Ray Charles and with the single-malt voice of Norah Jones featured as well? Again, Marsalis's arrangements for quintet are clever and swinging, astutely recasting familiar material in smart ways. And Nelson proves again that his laconic singing style is as much a child of Louis Armstrong as any proper "jazz" singer. Finally, this is the first we've gotten to hear Jones singing with a true jazz group behind (rather than merely her fine but limited pop band), and Marsalis spurs her singing to a higher realm. (Seriously, why hasn't Norah Jones made a real jazz album?)What's missing from Here We Go Again is pretty well implied by the title—it's a bit routine. You know these songs a little too well, and everyone involved is doing what they do perfectly on cue. This disc doesn't seem to have a capacity to surprise us.

That said, it's lovely in nearly every way—a great example of how jazz can still be a powerful popular medium. It's a jazz album that I think just about anyone should delight in.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)